I’m trying to write out my thoughts on Pacific Rim without simply restating Sam Keeper’s information-dense article “The Visual Intelligence of Pacific Rim” at Storming the Ivory Tower. So maybe you want to check that out.

Worse, I’m about to make many over-generalizations about things about which I know more than the average American, but I’m far from an expert in.

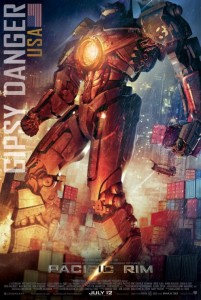

I saw Pacific Rim. (That’s not the generalization.) Friends learned this, and asked me my opinion. I’ve struggled. I’ve called it a “big, dumb giant robot movie,” “mecha vs. Godzilla,” and “fundamentally a Godzilla film.”

Here’s the thing: Japanese films are rooted in a certain style of visual storytelling. From kamishibai to manga to anime, Japanese storytelling revolves around imagery. Even Japanese novels include a lot of visual imagery, compared to the Western focus on dialogue. (And the over-generalizations begin…) We are Greek; they are Chinese.

This carries over into live-action film. Japanese films are low on dialogue, because you’re supposed to look at the film and understand what’s going on. Contrast this with, say, the scene in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace when Anakin flies the fighter into the space battle. He suddenly gets very talkative, calling out practically everything in his head. Japanese films rarely do this.

Sadly, film criticism in America focuses on dialogue. If there’s not much dialogue, the critic assumes that the film’s either shallow or “arty.” Imagery is seen mainly as an enhancer of emotion: dramatic lighting heightens tension, but cannot move the story forward.

This blinds critics to the visual storytelling of Pacific Rim. Because the film’s imagery focuses on giant robots punching giant monsters, it’s not an art film, thus it’s shallow.

Note: this is not about “paying attention.” This is about a fundamental approach to conveying information, that most Westerners just don’t see, and that Asians do. This explains the furor over Western comic book panels that set mood but “don’t move the story forward.” It explains much of why Hong Kong cinema bores most Americans to tears; because they’re not looking for the same things Asian audiences are looking for.

So. Pacific Rim conveys a lot with background details, with character stances and facial reactions. The Jaegers all have different designs. Nobody in the film explains why, because you’re supposed to figure it out by looking at them. Mako Mori is quiet, so we are told her story without words. We don’t need dialogue to understand it; we need to see her fight.

This strangeness doubles with the theme of social cohesion, which is emphasized to an extent Western audiences rarely see. We focus on loners–Becket, Mori, Pentecost–an action movie cliché. But they succeed in the end when they synchronize with others or allow others to synchronize. They win, not because of their determination or their desire for vengeance, but because of their social bonds.

One can enjoy Pacific Rim purely as a super robot movie. It paces itself cleanly and hits all the right beats as an action movie.

But it is not merely an action movie.